|

| William Walker |

The term National War in Central America refers to the combined military efforts of Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador to defeat the forces of Tennessee-born U.S. filibuster William Walker in 1856–57.

The Walker episode represented the pinnacle of 19th-century U.S. filibustering, or private mercenary efforts to invade, dominate, and govern territories in Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean Basin.

The war against Walker briefly united Central America’s fractious nation-states, while its aftermath ushered in a period of elite convergence and relative political stability in Nicaragua that endured into the early 20th century.

Nicaraguans tend to remember the Walker episode as the first instance of U.S. imperialist meddling in their country’s internal affairs, providing a touchstone for anti-imperialist and nationalist sentiments well into the 20th century. That popular memory also tends to suppress key features of a war that all observers agree left a deep imprint on isthmian history.

In early 1855 Nicaraguan Liberals, based in the city of León, contracted with the soldier of fortune Walker, the self-proclaimed “Grey-Eyed Man of Destiny,” in their ongoing civil conflict against that country’s Conservatives, based in the city of Granada.

The roots of the conflict between León’s Liberals and Granada’s Conservatives were complex, based on regional, political, and ideological divisions, and the efforts of elites in both regions to dominate the country’s post-independence state.

|

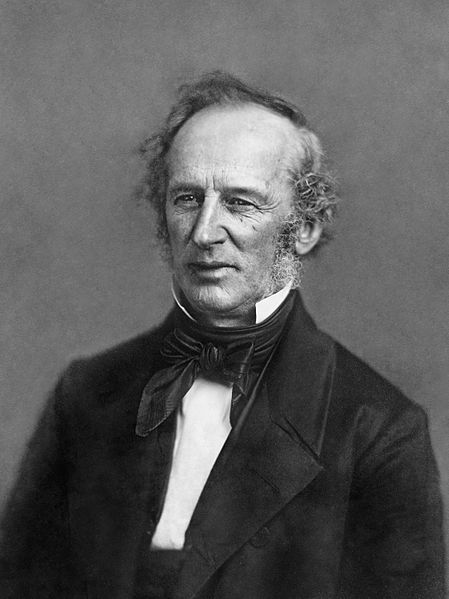

| Cornelius Vanderbilt |

The origins of Nicaraguan Liberals’s invitation to Walker can also be traced to their experience with U.S. travelers and businessmen in the transisthmian route across Nicaragua that developed in the wake of the California gold rush after 1849, most notably U.S. magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt’s Accessory Transit Company, which began operations in 1851.

The 31-year-old Walker had gained fame principally in his unsuccessful filibustering ventures in Baja California and Sonora, Mexico, in 1853–54. Offering Walker and his fellow mercenaries 250 acres of land each following the Conservatives’s defeat, León’s Liberals were shocked when, following his army’s victory in October 1855 and his usurpation of the presidency in July 1856, Walker launched a concerted effort to remake Nicaragua according to his own designs.

Reinstituting African slavery (abolished in 1824), he also sought to seize all state power, disfranchise the elites, confiscate elite properties, and transform the country into a Protestant slaveholding patrician society modeled on the U.S. South. His brazen power grab unified elites across Central America, who feared the loss of their own privileges and power.

Costa Rican forces, entering the country from the south, fought Walker’s forces in April 1856, followed in July by the invasion from the north of a combined army of over 1,000 Guatemalans, Salvadorans, and Hondurans.

A series of hard-fought battles followed, as Walker’s army, stung by the desertion of most native troops, retreated to its strongholds in Granada and Rivas. Hemmed in on all sides, Walker ordered the burning of Granada. For Nicaraguans, the complete destruction of the old colonial city by Walker’s drunken filibusters ranks among the most horrific and memorable episodes of the conflict.

With the crucial intervention of Cornelius Vanderbilt, with whom Walker had made a powerful enemy, Walker’s forces surrendered on May 1, 1857. He made three further attempts to reestablish his regime; during the last, in 1860, the British navy captured him and Honduran authorities executed him.

In Central America, the National War is chiefly remembered as the first instance of U.S. imperialist and military meddling on the isthmus—even though the U.S. government played only a marginal role in the conflict.

The war discredited Nicaragua’s Liberals, who joined Conservatives in a series of governments that led to the most peaceful and stable period in post-independence Nicaraguan history to that time. What Nicaraguans and Central Americans tend not to emphasize is the role of León’s Liberals in inviting Walker in the first place and the warm embrace he received during his first year.

The National War and its aftermath shaped isthmian politics in enduring ways, especially in fostering anti–United States nationalist sentiments and continue to occupy an important position in the collective memory of Central Americans, especially in Nicaragua.