|

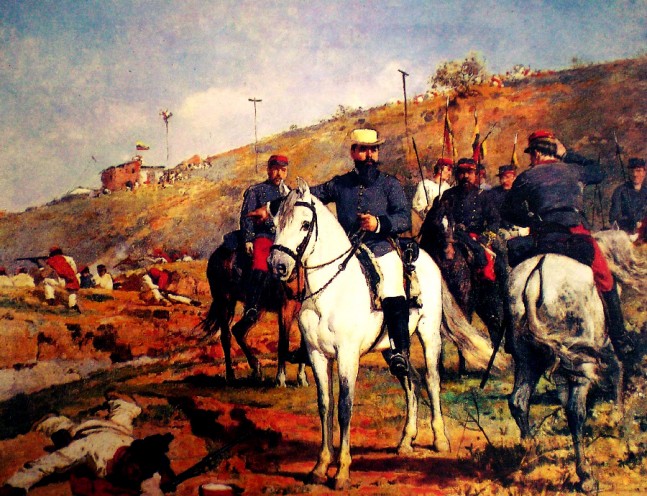

| Caudillos and Caudillismo |

Understanding the phenomenon of the caudillo is essential for understanding the political history of 19th-century Latin America. (The terms caudillismo and caudillaje refer to the more general phenomenon of rule by caudillos.)

While there is no universal definition that fits every caudillo under all circumstances, scholars generally agree on a cluster of attributes that most caudillos shared and that together provide a viable working definition of the caudillo phenomenon.

In general, a caudillo was a political-military strongman who wielded political authority and exercised political and military power by virtue of personal charisma, control of resources such as land and property, the personal loyalty of his followers and clients, reliance on extensive clientage networks, the capacity to dispense patronage and resources to clients, and personal control of the means of organized violence.

|

Some caudillos were also distinguished by their exceptional personal courage, physical prowess, or ability to lead men in battle. Many also displayed a kind of hypermasculinity and macho swagger that emphasized their maleness in explicitly sexualized terms.

In many ways, the keyword is personal: a caudillo was a type of leader, marked by his style of leadership, and most defined by the personal nature of his rule. Constitutions, state bureaucracies, representative assemblies, periodic elections—these and other institutional constraints on individual and personal power, commonly associated with modern state forms, all were antithetical to the caudillo style of rule, while also often coexisting in tension with it. Ideology mattered little, as caudillos ran the gamut from populist revolutionaries to moderate liberals to staunch conservatives.

There is broad agreement that the shorter-term origins of caudillismo can be traced to the tumult of the independence period, as local and regional military chieftains emerged in the fight against the Spanish.

A paradigmatic example is José Antonio Páez

At the opposite end of the spectrum from Páez, in terms of both his personal background and rise to power, was the Argentine caudillo Juan Manuel de Rosas

Scion of an elite porteño (Buenos Aires) Creole family, Rosas left the port city as a young man to become a cattle rancher and property owner in the pampas of the interior, living and working among the gauchos, from whom he demanded absolute obedience and loyalty, and among whom he developed his base of social support.

In this he represented the rising class of estancieros (estate owners) whose wealth and power were based not on inherited privilege or control of state offices but on control of land, men, and resources. Rosas did not participate in the independence battles against Spain but became a key player in the subsequent struggles that defined the shape of post-independence Argentina.

Rosas was opposed to the liberal, unitarian, modernizing regime of Bernardino Rivadavia

With his base of support secure, Rosas allied with the federalists who overthrew Rivadavia. Soon after, he became the governor of Buenos Aires and then absolute dictator. His style of leadership was profoundly personal: All power and authority flowed directly from him.

Dispensing favors and patronage to his loyal allies, he also terrorized his foes, in part through his feared mazorca (literally, “ears of corn”—effectively, “enforcers”), a kind of goon squad responsible for upward of 2,000 murders during his years in power. Rosas was overthrown and exiled in 1852.

Other 19th-century caudillos demonstrated variations on these general themes. The Mexican Creole and self-proclaimed founder of the republic and caudillo of independence José Antonio López de Santa Ana was first and foremost a political opportunist—beginning his career as a royalist army officer in the service of Spain, donning the mantle of pro-independence liberalism and federalism in the 1820s, and switching sides again to become a staunch conservative and centralist from the mid-1830s.

What remained consistent was his style of leadership: the cultivation of personal loyalty via the calculated dispensation of patronage and favors to clients and allies, the ruthless crushing of foes, and ostentatious displays and titles intended to glorify his person and inculcate unquestioned loyalty among his followers.

One could continue in this vein, identifying individual caudillos who came to dominate the political lives of their nations—the populist folk caudillo Rafael Carrera in Guatemala, the dictator Porfirio Díaz in Mexico, and many others.

Scholars have proposed various caudillo typologies, distinguishing between the cultured caudillo and the barbarous caudillo, for instance, or identifying the consular caudillo, the super caudillo, and the folk caudillo, among others. The multiplicity of types suggests the tremendous variability of the phenomenon.

Not all caudillos were national leaders, however. More often they remained lesser figures who dominated their own locales or regions—men like Juan Facundo Quiroga and Martín Güemes in the Argentine interior, Juan Nepomuceno Moreno of Colombia, and many others.

Not uncommonly, at local and regional levels, and in areas with substantial Indian populations, the phenomenon of the caudillo melded with that of the cacique, a local or regional political-military strongman, who deployed the same basic repertoire of techniques and styles of personalized rule and patronage-clientage to dominate regions, provinces, towns, and villages.

Indeed, the rule of national caudillos was predicated on the support of local and regional strongmen who served as their loyal and subordinate clients, who in turn dominated their own locales.

Thus there emerged in many areas a kind of hierarchical network of caudillo power, with the primary caudillo dominant over numerous lesser secondary caudillos, in turn dominant over numerous lesser tertiary caudillos, and so on down the chain of loyalty, alliance, and patronage-clientage.

Modernizing elites desirous of creating more modern state forms were among the most vociferous opponents of caudillo rule. A classic critique is the work of Argentine statesman and scholar Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, whose influential and scathing biography, Facundo (or, Civilizacion y barbarie, vida de Juan Facundo), first published in 1845, decried the rule of “primitive” caudillos like Facundo and Rosas, while framing the caudillo phenomenon in the broader context of the epic struggle between civilization and barbarism.

There is no scholarly consensus on when the caudillo phenomenon ended, or even if it has ended. Some point to the first half of the 19th century as the heyday of caudillos and caudillismo; others argue that the phenomenon continued into the 20th century and after, transmuting into various forms of populism and dictatorship, and manifest in the likes of Juan Perón

Despite vigorous debates over definitions, origins, periodization, and other aspects, however, few disagree that understanding the phenomenon of the caudillo and caudillismo is essential to understanding the political evolution of post-independence Latin America.