|

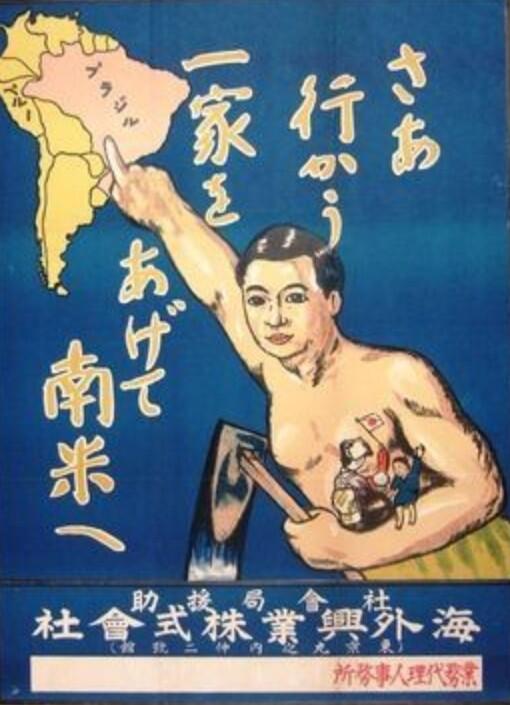

| A poster used in Japan to attract immigrants to Brazil |

There has been a long history of Asian migration to Latin America, with Chinese, Japanese, and Korean populations now in most countries in Central and South America. In addition there are also significant Indian communities in some countries, especially Guyana, and small numbers of Vietnamese.

The first links between the two areas may have been during the Ming dynasty in China, when some of the fleet of Chinese Admiral Cheng Ho may have reached the Americas. On many of his voyages members of the crew did not return with the fleet, and if any of his ships did reach the Americas, it seems likely that they would represent the first recent Asians to settle in the Americas.

It is also worth mentioning that in 1492, when Christopher Columbus sailed the Atlantic, he expected to reach Asia, and in 1519 Ferdinand Magellan started his voyage that was, after Magellan’s death, to circumnavigate the world, sailing through what became the Straits of Magellan across the Pacific Ocean, proving that it was possible to make the voyage.

|

However, there was little migration from Asia to the Americas until the early 19th century. Few Chinese ventured overseas during this period, except for those already in Southeast Asia—the Nanyang, as they called it.

In 1637 the Japanese government banned travel overseas and requested their citizens to return home; Korea was so isolated that travel was extremely difficult until recently. It is probable, however, that some Filipinos did settle in Latin America, especially in Peru, the center of Spanish power, as there were close shipping ties between Lima and Manila.

In the early 19th century the increased frequency of traveling overseas by ship and overpopulation in China saw many Chinese begin to migrate, initially to the favored destinations in Southeast Asia and around the Indian Ocean, and then to the Americas.

The California gold rush certainly saw many Chinese move to California and others moved in search of employment to Mexico and then to the Caribbean and South America. As a result, Chinese merchants started establishing businesses in cities and large towns along the Pacific coast. Some were farmers growing vegetables, others running shops, laundries, or restaurants.

A few Chinese families settled on the eastern coast of Latin America. A sizeable community was established in British Guiana (now Guyana), many working on plantations. The Chinese in British Guiana form the subject of novelist Robert Standish’s Mr. On Loong.

In addition, mention should be made of the family of Philip Hoalim from Guyana—Hoalim later became involved in politics in Singapore, forming the Malayan Democratic Union, the first political party ever established in Singapore.

As well as the Chinese in British Guiana, there was also a much larger Indian community. Known as the East Indians, to differentiate them from the West Indians, many spoke Hindi or Urdu, and there are numbers of Hindu temples and Muslim mosques in the capital of Georgetown. In neighboring Suriname, a former Dutch colony, there are also many East Indians and Chinese.

There is even a statue of Mohandas Gandhi in Paramaribo, Suriname’s capital. With its Dutch connections, there are also Indonesians (mainly from Java), many descending from indentured servants who came before the 1940s. Smaller Indian communities in Brazil, Paraguay, and northern Argentina have been instrumental in the introduction and breeding of zebu and Brahman cattle.

Chinese Communities

During the latter half of the 19th century, economic opportunities encouraged many Chinese to migrate to Cuba and Peru, where they worked on sugar plantations, in mining, and on haciendas, as well as running shops in townships. However, Cuba started to restrict the number of Chinese migrants. At the same time, the

Mexican government started encouraging migration from China. Porfirio Díaz, president 1876–80 and again 1884–1911, wanted Chinese coolies as a cheap labor force for building infrastructure in northern Mexico, where many settled.

As with the Chinese in Peru, there were gradual changes in the economic status of the migrant communities. Whereas in the 1870s most were manual laborers, by the 1900s many were running businesses.

By 1912 there were 35,000 Chinese in Mexico. Some used it as a route to the United States, but many others established businesses, often in poor suburbs. As a result, during periods of instability, especially during the Mexican Revolution, when rioting started, Asians were often the victims of mobs. The Mexican revolutionary hero Pancho Villa was definitely anti-Chinese, calling U.S. citizens Chino blanco (“white Chinese”).

When he took the town of Torreón on May 25, 1911, his forces and several thousand locals massacred 303 Chinese and five Japanese. When he was eventually defeated by Emilio Obregón, he is reported to have said “I would rather have been beaten by a Chinese than by Obregón.”

In February 1914 anti-Chinese riots took place in Cananea, and local Chinese took refuge in a U.S.-owned building, and in March 1915 many Chinese were attacked and robbed in rioting in Nogales. In spite of these attacks, many Chinese continued to migrate to Mexico, with 6,000 arriving in 1919–20. The Chinese community remains important in Mexico.

In Central America, there were small Chinese communities in each country, and most were involved in running small businesses. By the 1930s they had begun to dominate trade in many towns in El Salvador, so much so that the 1939 constitution included protections for indigenous small traders.

A new law, passed in March 1969, limited the running of small businesses in the country to people born in Central America, specifically excluding naturalized citizens.

However, many Chinese continued to operate with their businesses owned by middlemen. In Honduras, many small businesses were also owned by Chinese until the 1969 war with El Salvador, which led to fervent nationalism breaking out in the country and moves to reduce the number of Chinese-owned shops.

In Central America today there are small numbers of Vietnamese, and there is also a sizable Vietnamese population in Cuba, largely as a result of political ties between the two communist countries.

As well as in Peru, there are also significant Chinese communities in Brazil, Argentina, and Chile. Indeed bilateral ties and trade (with China) with all three countries have increased in recent years, offering many Chinese in Latin America new opportunities for establishing businesses.

Chinese-language gravestones can be seen in cemeteries throughout Latin America, although most seem to be located in foreign cemeteries, such as the British Cemetery at Chacarita in Buenos Aires or its counterparts in Chile.

Most Latin American countries now recognize the People’s Republic of China, but a few still extend diplomatic recognition to the Republic of China (Taiwan) as the legitimate government of the whole of China. For these, most ties are with Taiwan.

In Paraguay, the Taiwanese government and community plays an important role in commercial life in Asunción and has been involved in major projects, such as the refurbishment of the Paraguayan foreign ministry.

Japanese and Korean Settlers

In Brazil, the largest country in Latin America, there are many people of Chinese and East Indian ancestry and also some migrants from Malaysia involved in rubber cultivation. In the southern part of the country there are also increasing numbers of Japanese—there are said to be over 600,000 Brazilians with Japanese ancestry.

A number of the Japanese can trace their origins in Brazil back to 1908 when an agreement with the municipal authorities in São Paulo allowed Japanese to settle in the hinterland. They established many vegetable farms, and there are Japanese grocery stores, bookshops, and even geisha in São Paulo today.

There were also numbers of Japanese farmers who left Japan during this period, with many settling in Peru, Brazil, and Paraguay, where the government was encouraging foreigners to move to the country and establish colonies.

Many were poor Japanese in search of work, but quite a number were well educated. Some of the latter settled in Panama—a few involving themselves in businesses so closely linked to the Panama Canal that spying by them has long been alleged.

One of them, Yoshitaro Amano, a Japanese store owner who had lived in Panama City, spied on U.S. ships using the Panama Canal. He later fled Panama and was arrested for spying in Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and then Colombia.

Perhaps the most prominent example of the role of the Japanese in Latin America concerns two of the Japanese who left Kumamoto, Japan, moving to Peru in 1934: Naoichi Fujimori and his wife, Mutsue. Four years later their son, Alberto, was born, and the parents applied to the local Japanese consulate to ensure the child retained Japanese citizenship.

He worked as an agricultural engineer and became dean and then rector of his old university, also hosting a television show. In 1990 Fujimori, heading the Cambio 90 party (“Change 1990”), defeated the author Mario Vargas Llosa in the election for president in a surprise result.

Although he was Japanese, Fujimori gained the political nickname “el chino” (“the Chinese man”), with many observers crediting his victory with his ethnicity, which set him apart from the political elite of Spanish descent.

Fujimori had campaigned on a platform of “Work, technology, honesty” but in what became known as Fujishock, he instituted massive economic reforms and invested the office of the president with many new powers.

His wife, Susana Higuchi, also of Japanese descent, in a very public divorce, accused him of stealing from donations by Japanese foundations. Reelected in 1995, Fujimori won the 2000 election, but soon afterwards a massive corruption scandal emerged. Fujimori, overseas at the time, then went to Japan, where he resigned.

In November 2005 he flew from Japan to Chile and was arrested on his arrival. On September 22, 2007, he was extradited to Peru where he was jailed awaiting trial. On December 12, 2007, Fujimori was convicted of abuse of authority and sentenced to six years in prison.

He faces three other trials on charges including murder, kidnapping, and corruption. Fujimori remains the bestknown politician of Asian ancestry to hold high office in Latin America, but he has also become a by word for corruption and political sleaze.

Of the Koreans who have settled in Latin America, many run shops and small businesses. There are parts of Buenos Aires and also Rio de Janeiro with large Korean populations. In Uruguay there has been an influx of Koreans, many associated with Rev. Sun Myung Moon.

Despite the high-profile involvement of Fujimori in Peruvian politics, most of the Asians in Latin America shun media hype. Although many operate small businesses either importing Chinese merchandise or household consumer products into Latin America or run restaurants, a new generation of highly educated Asians fluent in Spanish is emerging, many of whom were born in Latin America.

They are starting to enter the professions of law, accountancy, and banking, many having totally assimilated into the communities in which they live. When Hu Jintao, the general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, visited Brazil, his first overseas visit after assuming the leadership of the People’s Republic of China, he was greeted by thousands of Brazilians of Chinese ancestry.