|

| Financial Panics in North America |

Several financial panics took place during the 19th century in America. The first major financial crisis happened in 1819, when widespread foreclosures, bank failures, unemployment, and a slump in agriculture and manufacturing marked the end of the economic expansion that followed the War of 1812.

The nationwide depression triggered by the panic of 1819 was the first widespread failure of the market economy, although the market had fluctuated locally since the 1790s.

Businesses went bankrupt when they could not pay their debts and thousands of workers lost their jobs. In Philadelphia, unemployment reached 75 percent, and 1,800 workers were imprisoned for debt. Unemployed people set up a tent city on the outskirts of Baltimore.

|

Different schools of economic thought gave different explanations for the panic of 1819. The Austrian school theorized that the U.S. government borrowed too heavily to finance the War of 1812 and it caused great pressure on specie—gold and silver coin—reserves and this led to a suspension of specie payments in 1814.

This suspension stimulated the founding of new banks and expanded the issue of new bank notes, giving the impression that the total supply of investment capital had increased. After the War of 1812, a boom, fueled by land speculation gripped the country and stimulated projects like turnpikes and farm-improvement vehicles.

Most people recognized the precarious monetary situation, but the banks could not return to a nationwide specie system. There was a wave of bankruptcies, bank failures, and bank runs. Prices dropped and urban unemployment rose to lofty heights.

In part, international events caused the panic of 1819. The Napoleonic Wars decimated agriculture and reduced the demand for American crops while war and revolution in the New World destroyed the precious metal supply line from Mexico and Peru to Europe.

Without the international money supply base, European governments hoarded all the available specie and this in turn caused American bankers and businessmen to start issuing false banknotes and expanding credit.

American bankers, inexperienced with corporate charters, promissory notes, bills of exchange, or stocks and bonds, encouraged the speculation boom during the first years of the market revolution.

By 1824 most of the panic had passed and the U.S. economy gradually recovered during the rest of the decade. The United States survived the panic of 1819, its first experience with the ups and downs of the business cycle.

Panic of 1837

|

| Financial panic of 1837 |

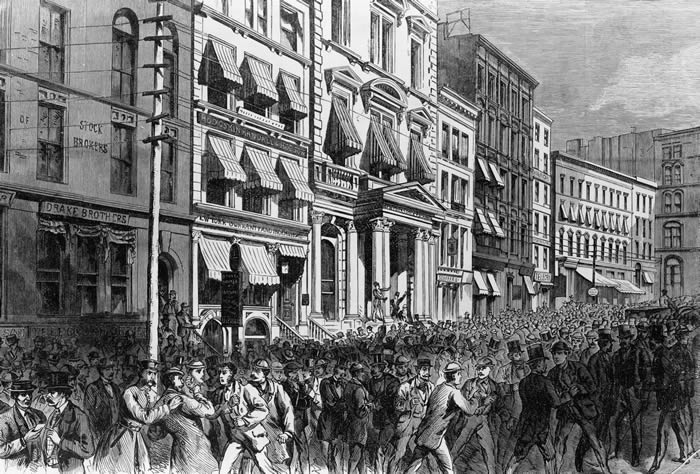

The next significant business crisis in the United States, the panic of 1837, was one of the most severe financial downturns in U.S. history. Speculative fever had infected all corners of the United States, and the bubble burst on May 10, 1837, in New York City when every bank stopped payment in specie.

A five-year depression followed as banks failed and unemployment reached record levels. This depression, interrupted by a brief recovery from 1838 to 1839, compared in severity and scope to the Great Depression of the 1930s and its monetary configurations also parallel the 1930s.

In both depressions many banks closed or merged, over one-quarter of them in 1837 and over one-third the number in the 1930s depression. Erratic and unwise government monetary policies played an important part in both depressions.

|

Panic of 1857

The United States gradually recovered from the panic of 1837 and entered a period of prosperity and speculation, following the Mexican-American War and the discovery of gold in California in the late 1840s.

Gold pouring into the American economy helped inflate the currency and produce a sudden downturn in 1857. The August 24, 1857, collapse of the New York City branch of the Ohio Life Insurance and Trust Company following a massive embezzlement set off the panic.

After this, a series of other setbacks shook American confidence, including the fall of grain prices, the decision of British investors to remove funds from U.S. banks, widespread railroad failures, and the collapse of land speculation programs that depended on new rail routes.

Over 5,000 businesses failed within a year and unemployment became widespread. The South was less hard hit than other regions because of the stability of the cotton market.

The Tariff Act of 1857 reduced the average rate to about 20 percent and became another of the major issues that increased tensions between the North and the South. The United States did not recover from the panic of 1857 for a full year and a half and its full impact did not fade until the American Civil War.

Panic of 1873

|

| Financial panics of 1973 |

The end of the Civil War produced a boom in railroad construction, with 35,000 miles of new tracks laid across the country between 1866 and 1873. The railroad industry, the nation’s largest employer at the time outside of agriculture, involved much money, risk, and speculation. Jay Cooke and Company, a Philadelphia banking firm, was just one of many that had invested and speculated in railroads.

When it closed it doors and declared bankruptcy on September 18, 1873, it helped trigger the panic of 1873. Eightynine of America’s 364 railroads went bankrupt and a total of 18,000 businesses failed between 1873 and 1875. The New York Stock Exchange closed for 10 days.

By 1876 unemployment had reached 14 percent and workers suffered until the depression lifted in the spring of 1879. The end of the panic coincided with the beginning of the waves of immigration that lasted until the early 1920s.

Panic of 1884

Speculation caused a stock market crash in 1884 that in turn caused an acute financial crisis called the panic of 1884. New York national banks, with the silent backing of the U.S. Treasury Department, halted investments in the remainder of the United States and called in outstanding loans.

The New York Clearing House Association bailed out banks at risk of failure, averting a larger crisis, but the investment firm Grant & Ward, Marine Bank of New York, Penn Banks of Pittsburgh, and over 10,000 other businesses failed.

Panic of 1893

Precipitated in part by a run on the gold supply, the panic of 1893 marked a serious decline in the U.S. economy. Economic historians believe that the panic of 1893 was the worst economic crisis in American history to that point and they draw attention to several possible causes for it.

Too many people tried to redeem silver notes for gold, eventually exceeding the limit for the minimum amount of gold in federal reserves and making U.S. notes for gold unredeemable. The Philadelphia and Reading Railroad went bankrupt, and the Northern Pacific Railway, the Union Pacific Railroad, and the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad failed.

The National Cordage Company, the most actively traded stock of the time, went into receivership, a series of bank failures followed, and the price of silver fell, as well as agriculture prices. A total of over 15,000 companies and 500 banks failed.

At the panic’s peak, about 18 percent of the workforce was unemployed, with the largest number of jobless people concentrated in the industrial cities and mill towns. Coxey’s Army, a group of unemployed men from Ohio and Pennsylvania, marched to Washington to demand relief. In 1894 a series of strikes swept over the country, including the Pullman Strike that shut down most of the transportation system.

The panic of 1893 merged into the panic of 1896, but this proved to be less serious than other panics of the era. It was caused by a drop in silver reserves and market anxiety about the effects that it would have on the gold standard. Commodities deflation drove the stock market to new lows, a trend that did not reverse until after William McKinley became president.

Stephen Williamson, associate professor of economics at Ottawa University, compared financial panics in Canada with those in the United States. He concluded in part that the Canadian banking system experienced fewer panics because it was better regulated and well diversified.