|

| American Temperance Movement |

When the first European settlers began arriving in North America in the 17th century, they brought their alcoholic beverages with them and soon found local ways to quench their thirst by using new raw materials like sugarcane. Fermented drinks like cider and beer and distilled ones like rum and whiskey were viewed by virtually all settlers as a gift from God.

These beverages protected drinkers from the dangers of tainted water and were perceived as both healthful and energizing. Men, women, and children drank, in varying quantities and strengths, from early morning to bedtime, at work and at play.

Drunkenness, however, was frowned on and was punishable in many colonies. Puritan cleric Increase Mather called liquor “a good creature of God ... but the Drunkard is from the Devil.” As rum became a significant moneymaker for the New World, Americans began distilling and drinking beverages with much higher alcohol content than colonials’ traditional tipples.

|

The introduction of homegrown corn and rye whiskeys also made it harder to keep drunkenness under control. In 1774 on the eve of the American Revolution, a Philadelphia Quaker called distilled liquor a “Mighty Destroyer” that was both unhealthy and immoral.

In 1784 famed physician and patriot Benjamin Rush attacked the health and moral deficiencies of “ardent,” or distilled spirits. Drinking these, he wrote, would surely lead to disease and what in modern times is called addiction.

Intemperance, Rush further argued, disrupted family and work life and was the enemy of those republican virtues on which the new nation had been founded and depended for its success.

Rush’s idea of restricting or even banning what was becoming known as “demon rum” seemed impossible at first but eventually became part of a larger pursuit of moral perfection in 19th-century America.

|

| Vote dry |

Although hard drinking increased between 1790 and the 1830s, new forces were at work. Temperance appealed especially to clergymen, mothers, health advocates, owners of factories, and builders of railroads whose new machines were getting faster and more complicated.

It would also strike a chord with native-born Americans fearful of the rising tide of Irish Roman Catholic immigrants and their presumed heavy drinking habits, and, to a lesser extent, Germans bringing their beer-making skills to America.

Presbyterian and Methodist religious leaders began agitating against strong drink in 1811. By 1826 a new organization, the American Temperance Society, called for abstinence from whiskey, but found no fault with moderate use of nondistilled beverages.

That same year, Congregationalist minister Lyman Beecher called for total abstinence from alcohol of any kind. Many agreed; rejecting alcohol entirely became known as teetotaling.

For the most part, early temperance efforts were spearheaded by religious and political elites, but there were exceptions. In 1840 six men, possibly while actually drinking in a Baltimore bar, created the Washington Temperance Society, a group that would help drinkers give up their unhealthful and immoral habit. In religious revival-like mass meetings, thousands of men pledged to stop drinking and a fair number fulfilled their promise.

In 1851 Maine became the first state to enact a law prohibiting the manufacture and sale of liquor. By 1855 a dozen states and two Canadian provinces had also adopted Maine laws. Between 1830 and the American Civil War, annual per capita consumption of alcohol by persons aged 15 and over fell from 7.1 gallons to 2.53 gallons.

The temperance movement suffered a setback when the impending breakup of the Union and the ensuing Civil War dominated public concern. With the war’s end, the drinking issue revived. Founded in 1869 by Civil War veterans, the Prohibition Party fielded its own presidential candidates in eight post–Civil War elections, never winning more than 2.2 percent of the vote, but helping to advance the cause.

More successfully, the Anti-Saloon League, founded by a minister in 1893, worked with both major parties to achieve its dry agenda through local-option elections and other techniques, paving the way to 20th-century prohibition.

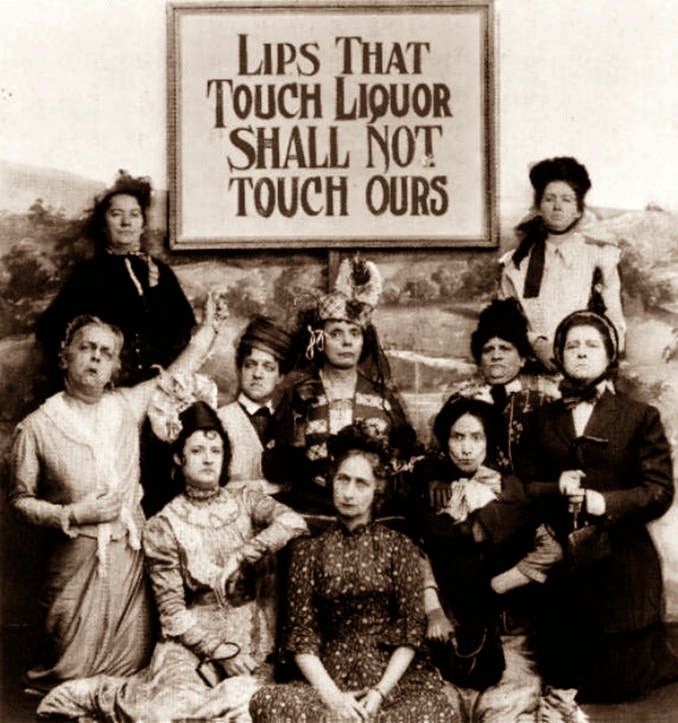

Most important was the 1874 emergence of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union. For the first time, large numbers of women, not yet able to vote, would play a leadership role in a major public controversy. Focusing on the evils of the neighborhood saloon, WCTU members began holding prayer meetings at places that purveyed alcohol.

The exploits of WCTU member Carrie Nation, a Kansan who wielded a hatchet to destroy saloons and smash whiskey bottles, became famous but were not typical of the organization’s strategies or goals.

Led by Frances E. Willard, a former women’s college president, the WCTU highlighted home protection against the disastrous effect that predominantly male drinking had on the women and children who depended on them.

The 150,000-member organization also campaigned successfully for antialcohol education in the nation’s public schools and sought drinking bans at federal facilities and on Indian reservations.

President Rutherford B. Hayes complied; lemonade was served at White House events. Anti-drinking propaganda, including songs, plays, and heartrending novels such as the famous Ten Nights in a Bar Room, helped spread a message of sobriety that could be assured only by public action.

By the time Frances Willard died in 1898, her WCTU, as well as the Prohibition Party and Anti-Saloon League, were closer to their goal than any could have known. Persuaded by political considerations and progressivist arguments, all brought into sharp focus by America’s entry into World War I, the nation implemented a farreaching prohibition on alcohol sale and use in 1920.