|

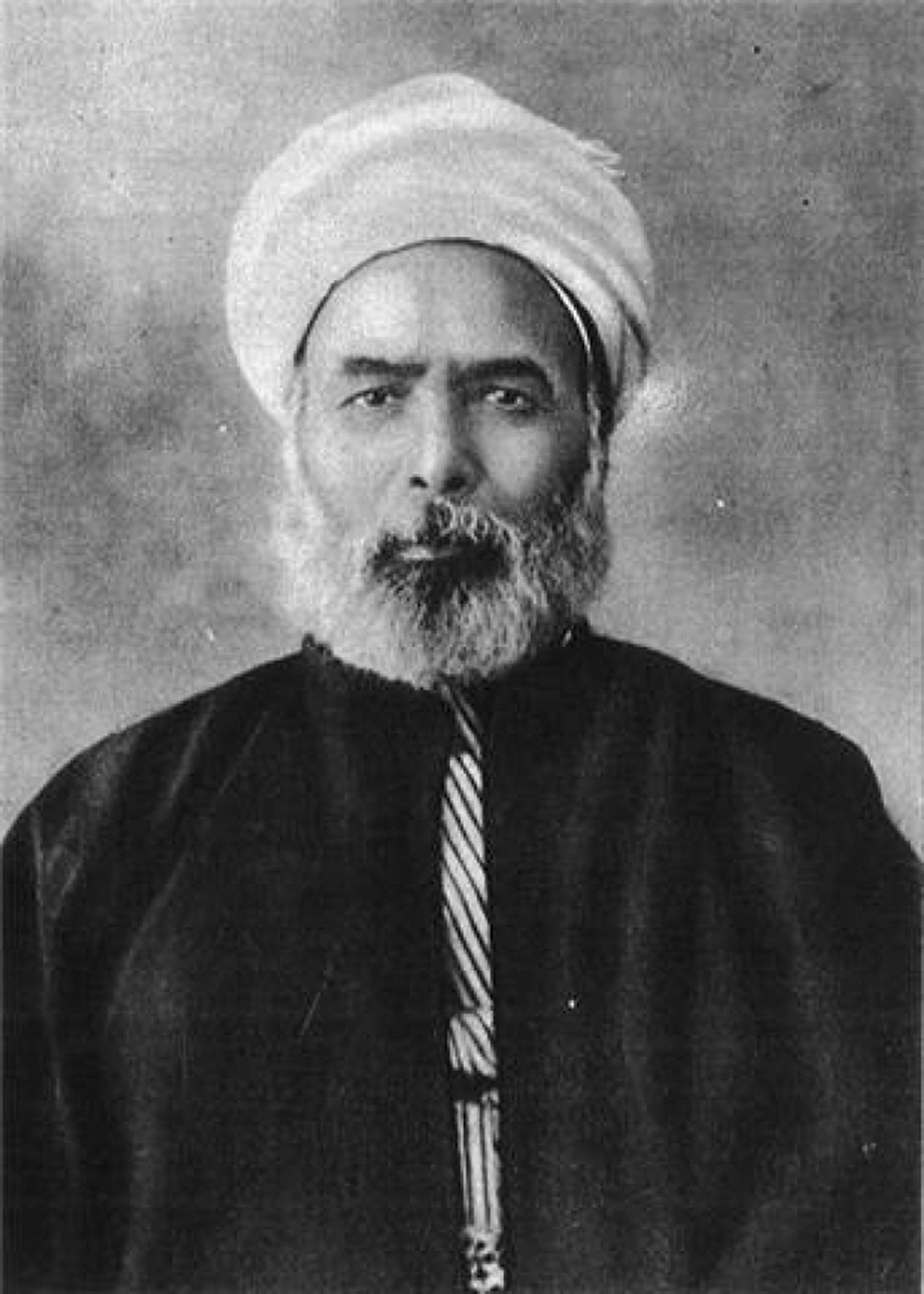

| Rifa’a al-Tahtawi |

During the 19th century a number of Arab intellectuals led the way for reforms and cultural changes in the Arab world. Rifa’a al-Tahtawi from Egypt was one of the first and foremost reformers. A graduate of esteemed Muslim university al-Azhar, Tahtawi was sent to France to study as part of Muhammad Ali’s modernizing program.

He returned to Egypt, where he served as director of the Royal School of Administration and School of Languages, was editor of the Official Gazette, and Director of Department of Translations.

Tahtawi published dozens of his own works as well as translations of French works into Arabic. In A Paris Profile, Tahtawi described his interactions as a Muslim Egyptian with French culture and society.

|

His account was an open-minded and balanced one, offering praise as well as criticism for many aspects of Western civilization. For example, Tahtawi respected French originality in the arts but was offended by public displays of drunkenness.

Tahtawi urged the study of the modern world and stressed the need of education for both boys and girls; he believed citizens needed to take an active role in building a civilized society.

Khayr al-Din, an Ottoman official from Tunisia, echoed Tahtawi’s emphasis on education while also addressing the problems of authoritarian rule. He advocated limiting the power of the sultan through law and consultation and wrote the first constitution in the Ottoman Empire.

The Egyptian writer Muhammad Abduh dealt with the ongoing question of how to become part of the modern world while remaining a Muslim. He was heavily influenced by the pan-Islamic thought of Jamal al-Din al-Afghani.

Abduh taught in Lebanon, traveled to Paris, and held several government positions in Egypt. He became mufti of Egypt in 1899 and was responsible for religious law and issued fatwas (legal opinions on disputed points of religious law).

|

| Muhammad Abduh |

Abduh became one of the most highly respected and revered figures in Egypt, although some conservatives opposed his reforms and open-mindedness while some more radical nationalists berated him for not being liberal enough.

In his publications, including Face to Face with Science and Civilizations and Memoirs, he urged the spiritual revival of the Muslim and Arab world, arguing that Islam was not incompatible with modern science and technology. He also stressed the importance not only of law but of reason in Islamic society.

Originally from Syria, Muhammad Rashid Rida was a follower of Abduh. He moved to Egypt and founded the highly respected journal al-Manar. His writings had a wide influence on Islamic thought, and he became one of the foremost spokespersons for what has become known as political Islam. Rida also discussed socialism and Bolshevism and the role religion should play in contemporary political life.

Egyptian Abdullah al-Nadim edited several satirical journals and was a staunch supporter of the Urabi revolt of 1881–82. He also knew Jamal al-Afghani. Al-Nadim was exiled to Istanbul after his fiery nationalist stance earned him the enmity of the British.

Al-Nadim spoke openly about the growth of the nation (watan) and was one of the first modern Egyptian nationalists. In 1899 Anis al-Jalis started an Egyptian magazine that carried articles dealing with the role of women in society.

A new educated elite emerged as graduates of the many government and other schools that had been established as part of the reforming era of the Tanzimat entered public life. In the Sudan, the British founded Gordon College to educate male youth for government service.

Other schools founded by missionaries included the Syrian Protestant College (American University of Beirut, AUB), the Jesuit University St. Joseph in Beirut, and various Russian Orthodox schools scattered throughout Greater Syria.

The Alliance Israelite sponsored schools for Jewish students throughout the Ottoman Empire. Separate mission schools were also established for girls. A spirit of outward-looking, pro-Western thought prevailed, and many of the elites had extensive experience with the Western world. Many were bilingual in French or English.

Nineteenth-century Arab intellectuals, many of whom were Christians, fostered a literary renaissance with a revival of interest in the Arabic language. Some sought to modernize Arabic prose and poetic styles.

Butrus Bustani was one of the era’s foremost experts in the Arabic language. He also wrote a multivolume encyclopedia with thoughtful entries on science and literature as well as history. Numerous newspapers were published, especially in Cairo and Beirut.

Al-Muqtataf produced in Cairo by Yacoub Sarruf and Faris Nimr was one of the most famous. In 1875 the Taqla family founded al-Ahram, which became the premier newspaper in the Arab world. Many of these new journals were published in Egypt, where there was greater freedom of the press afforded by the British than in Ottoman controlled provinces.

Nationalism spread around the world in the 19th century, and the Arab provinces were no exception. A generation of Arab nationalists began to talk and write about the relationship of the Arabs within the Ottoman Empire and the role religion should and did play in modern nationalism. These early nationalists did not deny the importance of religion but used nationalism as their point of reference.

The first group that dealt with the controversial issue of separation from the Ottoman Empire on the basis of national identity was formed at the Syrian Protestant College in Beirut in 1847. Its members, who met secretly to avoid prosecution from the Ottoman intelligence services, included Faris Nimr.

They met under the guise of being a literary society; while the members did discuss literature they also delved into the important political questions facing the declining Ottoman Empire as well as the emergence of nascent Arab nationalism.

Various groups continued to meet at the college from 1847 to 1868 when a Beirut society began. Its members discussed the key political issues of Arab identity. The so-called Darwin affair of 1882 caused a number of the leading figures of the movement to leave the college.

In a public address, Dr. Edwin Lewis, a professor at the college, discussed Darwin’s theory of evolution; his positive conclusions about Darwin’s controversial theory roused the enmity of conservative American Christians on campus.

They attacked Lewis in print and forced his resignation. Several of the liberal Arab junior faculty, including Nimr and Sarruf, resigned in outrage and moved to Cairo, where they became leading figures among Christian Arab secularists.

Abd al-Rahman al-Kawakibi was born in Syria, but after his writings about Arab identity roused the enmity of Khedive Abbas Hilmi, he left Syria and became a frequent contributor to al-Manar, the journal edited by Rashid Rida.

In his writings, Kawakibi discussed the key role of the Arabs in Islam; he also described the decadence and weaknesses of the Ottoman Empire. He stressed the importance of Arab unity. Another Arab nationalist, Jurji Zaidan, wrote for the journal al-Hilal.

Whereas pan-Islamists, such as al-Afghani, believed in the supremacy and integrity of the Islamic legacy, panArabists like Zaidan emphasized its uniquely Arab character and the importance of history, language, and culture over religion. The ideas of these early Arab nationalists would come to fruition with World War I and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire in the early 20th century.