|

| British Empire in Southern Africa |

The first British involvements in South Africa were a result of maritime traffic going around the Cape of Good Hope to India. In the 17th century, the British East India Company had established trading stations at Madras, Bombay, and Calcutta.

By the 18th century, a thriving trade led the British East India Company to have its own navy to carry goods and personnel back and forth from England to India.

In 1652 the Dutch East India Company founded a trading station near what is now Cape Town and was busy attempting to extend its settlement into the interior, in the face of opposition from the indigenous African tribes.

|

The wars of the French Revolution began in 1792, and the Netherlands was conquered and occupied by the French. To the British, with their unparalleled Royal Navy and need for a way station to India, the Dutch colony at Cape Town was a tempting target. In 1806 the British captured Cape Town and kept it even after Napoleon I’s final defeat in 1815.

British Expansion

As the years progressed, the British became intent on making the colony more British; English replaced Dutch as the official language of the colony and its government. Anglican missionaries came to convert the Boers, the descendants of the Dutch settlers, to Anglicanism. (The Boers were staunch Calvinists of the Dutch Reformed Church.)

The missionaries also advocated the abolition of slavery. Indeed, due to the influence of the London Missionary Society, slavery was virtually abolished in South Africa even before it was in the empire as a whole in 1833.

|

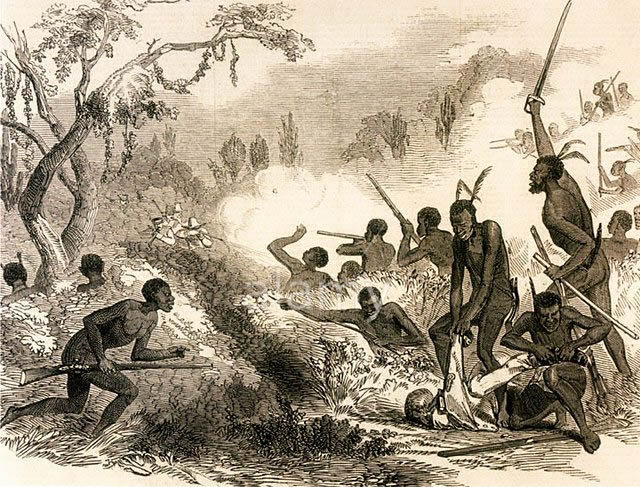

| Native Xhosa warrior |

With wars against indigenous tribes an ongoing struggle for European settlements in the area, the British did not wish to take on any new imperial responsibilities in South Africa. The Kaffir Wars waged between the Europeans and the native Xhosa people were particularly lengthy and brutal.

Consequently, between 1852 and 1854 the British government recognized two Boer republics, the Orange Free State, named for the Orange River, and the Transvaal Republic, on the opposite side of the Vaal River. In 1853 the Convention of Bloemfontein formalized, at least for the time being, the British relationship with the Boers.

Indeed, the entire government of South Africa was reorganized when in 1853 an Order in Council for Queen Victoria established fully representative government in the Cape Colony, with a parliament set up in Cape Town.

In 1877 the imperialist prime minister Benjamin Disraeli expanded the Cape Colony with the annexation of the Boer Transvaal Republic. He sent out a new governor of Cape Colony to oversee the process in the colony: Sir Henry Edward Bartle Frere, who arrived in Cape Town in April 1877.

The ninth, and final, Kaffir War broke out in October 1877, and although it ended with the defeat of the Africans, Frere was still alarmed. In Frere’s view, the most immediate problem lay in the relations with the Zulu Kingdom, now under King Cetewayo.

Frere felt that the presence of the Zulu Kingdom, with its 50,000-man army, had to be dealt with by force. On January 11, 1879, British commander Chelmsford’s South African Field Force crossed the border into Zululand. Early on the morning of January 22, Chelmsford set off after the Zulu regiments.

He left a force to hold Isandhlwana, the main force of which was the 1st Battalion of the 24th Regiment. The Zulus, some 20,000 strong, pounced on the force left behind at Isandhlwana; not one British soldier was left alive. From there, the Zulu advanced to a garrison that was mostly from the 2nd Battalion. After 12 hours of fighting, the Zulu retreated.

On March 28, 1879, the British, fighting the Zulu at Hlobane, narrowly escaped another disaster like Isandhlwana. Almost immediately, plans were made to reenter Zululand; the image of a victorious Cetewayo was more than the London government could tolerate. On May 31 Chelmsford again advanced into Zululand, determined on a final conquest to redeem himself for his fatal miscalculation at Isandhlwana.

On July 4, Chelmsford attacked Cetewayo’s royal kraal at Ulundi and crushed the Zulu regiments. Cetewayo was captured on August 28, 1879, but Queen Victoria intervened to free him in 1883. On February 8, 1884, Cetewayo died amid rumors he had been poisoned.

Agitation for Freedom

Ironically, the removal of the Zulu threat did not mean peace for British South Africa. After the war, the Transvaal Boers began to agitate again for their freedom, taken from them by Shepstone’s annexation in 1877. On December 12, 1880, they united to fight for their independence.

The British forces were unprepared for the superior marksmanship, modern weapons, and guerrilla tactics employed by the men of the Boer commandos. Prime Minister William Gladstone, opposed to the imperialist philosophy of his rival Benjamin Disraeli, made peace with the Boers. By August 8, 1881, the Boers ruled again in the Transvaal capital of Pretoria. In 1871 diamonds were discovered in the Cape

Colony. One of those caught up in the diamond rush was Cecil Rhodes. In 1881 he founded the De Beers Diamond Company. Pressing north into native African country (and away from stronger Boer resistance), Rhodes was instrumental in the annexation of Bechuanaland, today’s Botswana, in 1885. His primacy among those in the Cape Colony was recognized in 1890 when he became prime minister of the Cape Colony.

Coveting the possible diamond hoard in the Transvaal, Rhodes sent Leander Starr Jameson, his assistant during prior wars, on a raid into the Transvaal Republic on December 29, 1895.

Jameson and his men were quickly arrested and handed over to the British for trial and sentencing. For Rhodes, the punishment was more embarrassing; in 1896 he was forced to resign as prime minister for the Cape Colony.

The Jameson Raid seemed to the Boers another British attempt to conquer them and end their independence once and for all. In 1897 Joseph Chamberlain, the colonial secretary, or secretary of state for the colonies, appointed the ardent imperialist Alfred Milner as high commissioner for South Africa.

His views on empire were very similar to Frere’s. Instead of the Zulus, Milner saw the Boers as the main threat to British rule in South Africa. The British prime minister, Robert Cecil, Lord Salisbury, was an ardent empire-builder. While sporadic negotiations continued, both sides prepared for war, and Chamberlain sent reinforcements from England.

Paul Kruger, a leader of the Boer resistance, determined to strike before the reinforcements could arrive. He issued an ultimatum, which would expire on October 11, 1899. This saved the British the trouble— and the blame—of declaring war themselves.

Kruger followed his ultimatum with a lightning advance by his commandos into both the Cape Colony and Natal Province. Kruger had 88,000 men and knew the British only had 20,000.

However, Kruger underestimated the immense forces the British Empire had available. According to some estimates, by the end of the war, the British Empire committed a staggering 450,000 men to fight the Boers.

The British forces in South Africa were commanded by General Sir Redvers Buller, who proved to be a disappointing commanding officer. Time and again, he and his troops were defeated.

On January 10, 1900, General Frederick Sleigh Roberts arrived in South Africa to replace the befuddled Buller. Roberts immediately went on the offensive against the Boers. Roberts led the British to victory on February 27 and 28, and March 13, and on May 27, 1900, he entered the Transvaal, determined to bring the war to a conclusion.

On June 2 Kruger retreated from the capital of Pretoria, which Roberts entered in triumph three days later. The defeat of the Boer armies was sealed when Buller arrived in the Transvaal from Natal on June 12.

Between August 21 and 27 the last major battle of the war took place when Roberts and Buller defeated Boer general Louis Botha at Bergendal. In December 1900, with formal hostilities over, Roberts returned to Britain to become commander in chief of the army.

Roberts’s second-in-command, Kitchener, was left to oversee what soon became a guerrilla conflict. He adopted a draconian policy to stop the commandos, ordering his men to burn down Boer homesteads, destroy their crops, and run off or kill their livestock.

Kitchener introduced concentration camps in which to hold the dispossessed Boer families of the commandos. The conditions of the camps were appalling, and disease was endemic. According to some estimates, 28,000 Boers died in 46 camps, and between 14,000 and 20,000 Africans died in the camps.

At the same time, the movement of the Boer commandos was hampered by a series of armored blockhouses. On January 28, 1901, Kitchener began a series of fierce offensives designed to wear down the commandos in a battle of attrition. On May 31, 1902, a peace settlement was made bringing the war to an end at Vereeniging.

The Boers had been defeated on the battlefield, but had retained their independent spirit. Just two months earlier, on March 26, 1902, Rhodes had died, to be buried in his beloved Rhodesia. As a new century opened, a new and unknown future began for the British in South Africa.