|

| War of the Pacific (1877 - 1883) |

Sparked by conflicts over control of the rich nitrate fields in the Atacama Desert along South America’s Pacific coast, the War of the Pacific proved a national humiliation for the allies Peru and Bolivia and a national triumph for Chile. With its decisive victory, Chile wrested from Bolivia Antofagasta, its only access to the sea, thus rendering the country landlocked and shearing off Peru’s southernmost province of Tarapacá.

The strip of land conquered by Chile was loaded not with one but two vital natural resources, nitrates and copper, that later proved crucial in the development of the Chilean national economy. The war caused lasting resentment against Chile by its two defeated neighbors that endures to this day.

It also sparked a popular uprising in the Peruvian highlands that exposed the weak sense of national belonging among Peru’s highland Indian, black, and Chinese populations, and that for a time threatened to fragment Peru into warring regions.

|

Some scholars maintain that the ideology espoused by the highland rebels was itself explicitly nationalist, spearhead of a nationalist project directly at odds with the elitist nationalist discourse emanating from the capital, Lima.

This was just as the Peruvian national state and the Lima-based commercial elite were experiencing a deep fiscal crisis in consequence of the depletion of Peru’s guano reserves following the age of guano.

The war’s short-term trigger was Bolivia’s 1878 imposition of higher taxes on Chilean nitrate operations in the Bolivian province of Antofagasta, contrary to an earlier agreement between the two countries. Chile balked, tensions escalated, and soon Peru was drawn into the conflict in consequence of its secret mutual defense treaty with Bolivia.

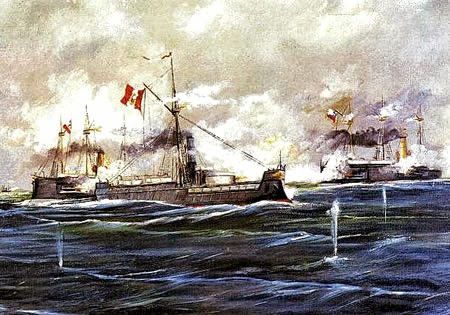

Hostilities commenced in April 1879 with a series of sea battles that raged along the Pacific coast. In the 1870s both nations had recently built formidable modern navies, though Chile’s proved far superior, destroying Peru’s in six months.

The decisive encounter was the Battle of Angamos of October 8, 1879, in which the Chileans captured the Peruvian battleship Huascar and killed its able commander, Miguel Grau. With its control of the sea secure, and with Bolivia knocked out of the picture, Chile launched a land invasion of Peru.

Following its January 1881 victories in the Battles of San Juan and Miraflores, the Chilean army occupied Lima and ousted the dictatorship backed by the Peruvian caudillo Nicolás de Piérola, installing a government headed by Francisco García Calderón.

For nearly three years following Chile’s capture of Lima, the Peruvian General Andrés Cáceres led an armed resistance to Chilean occupation in the central and southern Peruvian highlands, backed by an insurgent army of Indian, black, and Chinese workers and peasants, the montoneras.

Soon the army nominally headed by Cáceres fractured, as the montoneras and other groups pressed their own agendas that had less to do with ousting the Chilean occupiers than with overturning longstanding relations of power and privilege in the highlands, especially with regard to the region’s highly unequal patterns of landownership and labor relations.

Drawing on social memories of highland resistance during the Great Civil War a century earlier, the rebels kept up their resistance even after the war’s formal end in the Treaty of Ancón of October 1883.

Scholarly debates continue regarding the nature of this resistance movement, particularly its social composition, geographic extent, and the motivations of its participants in various regions, as expressed in both their written texts and collective actions.

The montonera movement highlights a broader pattern in Latin American history, in which fights among dominant groups lead to sustained challenges to existing social relations by those from below.