|

| Ultramontanism |

Ultramontanism literally means “over the mountains,” and it implies that there are two views of how the Catholic Church should be governed. One view sees leadership as a centralized and unified papacy (in Rome, over the Alps from the rest of Europe) and the other looks for local control and a national church (the church of France or Germany or any other country). Ultramontanism is the former view; Gallicanism is the latter.

For centuries, theologians had speculated on the position and authority of the Roman papacy, and often the pope was seen as the center and coordinator of the whole church. The urgency of these thoughts became apparent as the Protestant reformation began and challenged church unity.

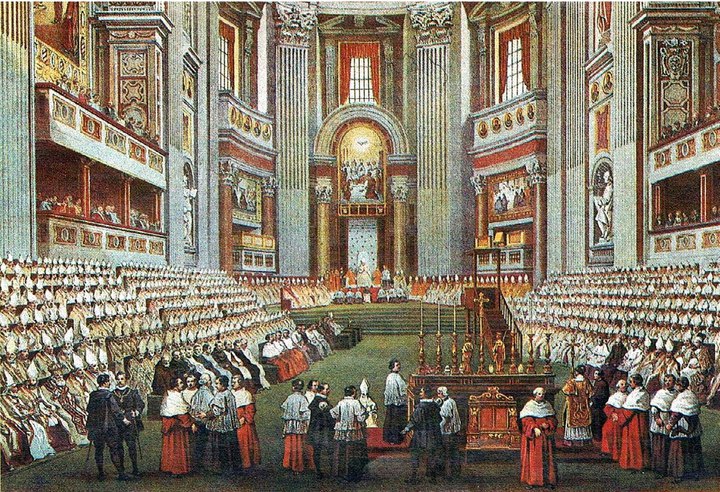

The first phase of ultramontanism is often called Romanism. It was promulgated by the forces of the Counter-Reformation and later championed by Robert Bellarmine. The bishops of the Council of Trent swallowed their objections to the claims of the papacy if only to stem the tide of Protestant defections among their flocks. Ironically, Trent reformed the Catholic Church by depositing even greater powers in the pope.

Momentum returned to the Catholic Church as a result of Romanist ultramontanism. All countries adopted it at least externally, even the actively independent regions of France and Germany. The Jesuit order served Romanism well, with its worldwide efforts to propagate the Catholic faith now held together by a focus on the pope.

Some of its characteristics include a strong hierarchy; a restriction of access to foundational texts like the Bible, the liturgy, and even theological texts; a folk piety that celebrated feasts, the “Sacred Heart,” and Marian devotions; and an expansionistic faith opposed to toleration of sects and supportive of conversions.

As time went on, the Romanists lost ground to the Gallicanism, as promoted by the likes of Louis XIV of France. At this time the word ultramontanism came into parlance, as national church identities revived and the enthusiasm of the Protestants waned. All this changed with the French Revolution, when the monarchy and its Gallican agents were deposed.

Again, the need for a strong papacy was felt, giving birth to the next phase called neo-ultramontanism. Many Catholics believed that the French Revolution’s anticlericalism and godless ideology were a direct result of the Protestant reformation as intensified later by the Enlightenment. This phase witnessed at times flirtation with liberal ideals of democracy among the laity, but with the revolutions of 1848, ultramontanism became soundly autocratic in its support of the papacy.

Pope Pius IX led the Catholic Church into the first Vatican I Council and rejected not only Gallicanism but all forms of liberal Catholicism. Among the ultramontanist positions it adopted were an emphasis on the juridical role of the pope over his supernatural role, more emotional devotions toward such things as the Blessed Sacrament and the Virgin Mary, a focus on Marian apparitions and pilgrimages, and attention on the centralized and authoritative church under the pope.

Between Vatican I and Vatican II, ultramontanism was effectively synonymous with orthodox Catholicism. Today the victory is so complete that the term has largely fallen out of usage.