|

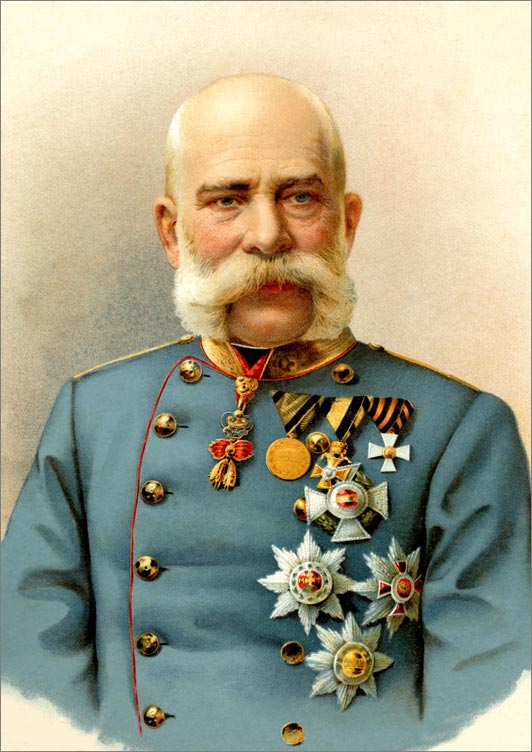

| Franz Josef |

The emperor of Austria, the apostolic king of Hungary, and the king of Bohemia from 1848 until 1916, Franz Josef I presided over the long decline of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, leading his nation into World War I. His reign of 68 years was only surpassed in Europe by those of Louis XIV of France and John II, prince of Liechtenstein.

Franz Josef was born on August 18, 1830, at the Schönbrunn Palace in Vienna, the capital of the empire. His grandfather was the late emperor Franz; his father was Archduke Franz; and his uncle was the ruling emperor Ferdinand.

His mother, Princess Sophie of Bavaria

|

In 1848, following the resignation of Chancellor Prince Metternich, Franz Josef was appointed governor of Bohemia but never took up the position, being sent to Italy, where he fought alongside Field Marshal Radetzky.

In July 1848 the Austrians defeated the Italians at the Battle of Custozza

Ferdinand I abdicated on December 2, and when his brother Franz Karl renounced the throne the crown passed to Franz Karl’s eldest son, Franz Josef, who used both names in his title to try to hark back to Emperor Josef (Joseph) II. It was during these relocations that Prince Franz Josef met Elisabeth, his cousin, who would later became his wife.

At 18, Franz Josef was guided by Prince Felix Schwarzenberg

King Charles Albert of Sardinia/Savoy used the Austrian preoccupation with Hungary as a good time to attack Austria, starting in March 1849. Radetzky defeated the Savoyards at the Battle of Novara and with Russian aid was able to crush the Hungarian revolt.

With the end of that crisis, Franz Josef suspended the 1849 constitution and appointed Alexander Bach, the former minister of the interior, to preside over a restoration of absolutist centralism.

Prince Schwarzenberg’s main aim was to try to stop the German Federation being controlled by Prussia. He wanted Austria to remain as the major power in central Europe, and Franz Josef certainly went along with this.

However, Schwarzenberg died in 1852, and unable to find anybody of his caliber, the emperor took over the day-to-day running of the country, with Karl Ferdinand Count von Buol-Schauenstein as prime minister, a position he held until 1859. Alexander Bach worked on domestic affairs, and Count Grünne on military affairs. In

itially, the main problem that Franz Josef faced was how to deal with Russia, which had supported the Austrians over the Hungarian rebellion in 1848. The Russians expected that this was the start of a new alliance. When the Crimean War broke out, the Austrians had to decide whether they would support their new ally, Russia, or their old one, France.

Franz Josef finally decided that neutrality was the best course, but the Russians, not trusting him, left an army on the Galician front. This meant that at the Peace of Paris at the end of the Crimean War, the Russians felt the Austrians had been ungrateful, yet the British and the French also felt that they could not trust them.

Three years after the Crimean War ended, the Austro-Sardinian War of 1859 broke out, with Count Cavour of Sardinia/Savoy managing to get support from Napoleon III of France.

Franz Josef personally led the Austrian soldiers at the Battle of Solferino and saw his army break and flee. This resulted in the Austrians losing control of Lombardy. The reunification of Italy presented Franz Josef with a strong neighbor to the south. The next war was with Prussia in 1866.

At the Battle of Königgrätz (Sadowa), the large Prussian army defeated an equally large Austrian and Saxon army; there were heavy casualties on both sides, but superior Prussian weaponry carried the day. With Italy supporting the Prussians at the peace agreement at the end of the war, the Austrians lost control of Venice.

Less Powerful Austria

At the end of the Austro-Prussian War of 1866, Franz Josef found himself ruling a far less powerful Austria, without its Italian possessions and with Prussia dominating Germany. Franz Josef had wanted to modernize and centralize his possessions but was forced to agree to the exact opposite.

The restructuring of the Habsburg possessions led to the establishment of the Austrian-Hungarian dualism in 1867. The Hungarian Compromise of 1867 saw Franz Josef as emperor of Austria and king of Hungary, although Hungary would retain its own parliament and prime minister.

Thus the Habsburg Empire would become the dual monarchy of Austro-Hungary, which would share the person of the emperor, the army, a joint minister for foreign affairs, and some financial offices.

For most of the rest of Franz Josef’s reign, the Austro-Hungarian Empire was in decline. Franz Josef’s mother had wanted him to marry Helene, the eldest daughter of her sister Ludovika.

However, he fell in love with Helene’s younger sister Elisabeth, who was only 16, and they were married in 1854. Their first child, Sophie, died as an infant, and their only son, Crown Prince Rudolf, died in 1889, allegedly by suicide, in the Mayerling incident.

Both of these were viewed at the time as divine retribution, although Franz Josef’s other daughters did outlive him. Franz Josef’s younger brother, Maximilian, became emperor of Mexico and was deposed and executed by firing squad there in 1867.

Franz Josef, although he had separated from her, was attached to his wife, and when she was stabbed to death in Geneva, Switzerland, in 1898 by an Italian anarchist, he never recovered.

The defeat of France in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 ensured that Austria could never manage to gain control of the German states that merged with Prussia to form the German Empire.

Trying to reposition Austria, from the late 1880s, Franz Josef slowly moved Austro-Hungary into an alliance with Germany and oversaw the occupation of Bosnia Herzegovina from 1878 and its annexation in 1908. This was to involve the Austro-Hungarian Empire heavily in the Balkans, bringing about the enmity of Russia, which had strong cultural ties with the Serbs.

During the latter part of his reign, Franz Josef did manage to modernize much of the empire. The opera house was built in Vienna starting in 1861, and the new Burgtheater, university, parliament building, town hall, and museums of art and natural history were all built.

In 1873 an economic crisis hit most of Europe, but Austria survived relatively well, being able to show the splendor of the Habsburg lands in the World Exhibition at the Prater in Vienna.

The railway network was heavily expanded, the telegraph system built, and in 1879 the first telephone system was installed. Franz Josef was persuaded to install a telephone on his desk at the Hofburg in Vienna, but it remained a fashion accessory, and there is little evidence of him actually using it until 1914.

Road to War

Franz Josef never liked his nephew and heir, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, and was particularly angered by the younger man’s marriage to Countess Sophie Chotek, who was not from a royal house.

Franz Ferdinand had insisted on the marriage, which had to be a morganatic one, with Sophie to become a consort rather than queen, when Franz Ferdinand succeeded his uncle. Franz Ferdinand was assassinated in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914, and Franz Josef was persuaded to declare war on Serbia on July 28, leading Austria into war.

The Austrian army was a multinational and multilingual one, reflecting the diversity of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Led by Austrians, it included Hungarians, Bosnians, Croatians, Czechs, Poles, and Slovaks. Although Franz Josef knew that it would not be an easy victory, his generals felt that it would not take long to capture Serbia.

They were able to defeat the Serbian armies and capture the country, but the soldiers quickly succumbed in guerrilla attacks and to disease. Franz Josef died on November 21, 1916, in the middle of World War I. He was succeeded by his nephew Karl I.