|

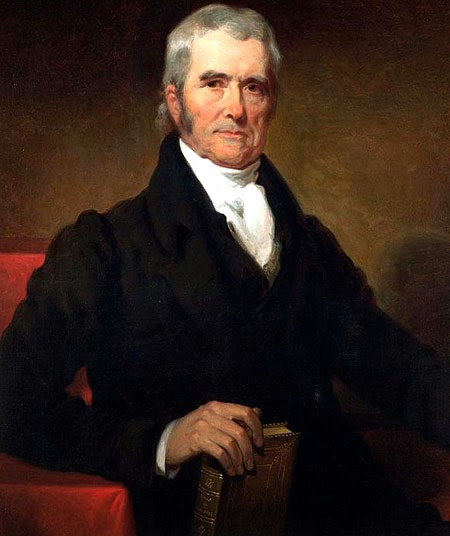

| John Marshall |

John Marshall, one of the most influential members of the Supreme Court in its earliest years, was born in Germantown, Virginia, in 1755 to Thomas and Mary Isham Keith Marshall.

At 18 Marshall began studying law, but temporarily abandoned it when his state joined the rebellion against Great Britain. After enlisting he saw action in numerous battles, but returned to the study of law when his term of enlistment ended in 1780, and he entered private practice the next year.

Marshall’s political career was filled with nominations and resignations, as he repeatedly tried to reject appointments or resign to return to his legal practice. He was elected to the Virginia House of Delegates in 1782, but resigned in 1784.

In 1788, he was part of the Virginia convention that was debating ratification of the U.S. Constitution, where he argued strenuously for acceptance on the basis that the states needed a stronger national government to survive. After the convention, he returned to his legal practice.

In 1795 President George Washington tried to convince Marshall to become attorney general and the next year ambassador to France, but Marshall declined both times. President John Adams was able to convince Marshall to serve as one of the ambassadors to France in 1797 where he became embroiled in what was later called the XYZ affair.

However, Adams was unable to secure Marshall’s agreement to accept the position of associate justice on the Supreme Court in 1798. Patrick Henry convinced Marshall to run for a federal office, and he was elected to the House of Representatives in 1799.

The next year President Adams wanted to nominate Marshall as secretary of war, but Marshall had little interest; when Adams later asked him to serve as secretary of state, however, Marshall accepted.

When Adams lost his bid for reelection to the presidency in 1800, he sought ways to ensure that a strong Federalist presence would remain, especially in the judiciary. With this in mind, he nominated Marshall as chief justice of the Supreme Court on January 20, 1801.

Marshall continued serving as secretary of state and oversaw other of Adams’s midnight appointments that so enraged Jefferson and his Republicans. It was these appointments that brought the first major case before Marshall during his tenure on the Supreme Court.

In 1803 Marbury v. Madison gave Marshall his first opportunity to flex his judicial muscles. The case centered on the appointment of certain judges and other positions by President Adams, approved by Congress, signed and sealed by the president, but left undelivered. The conflict became whether or not the appointments were official.

Marbury claimed that since his appointment as justice of the peace in the District of Columbia had been made, it was a valid appointment whether or not it had been delivered to him officially. Incoming president Thomas Jefferson, however, believed that since such appointments only became official upon delivery, those that had remained undelivered were void.

Thus, attempting to block as many of these lastminute appointments as he could, he instructed new secretary of state James Madison to leave the appointments undelivered. It was in this case that Marshall first elaborated the idea of judicial review.

In the Court’s decision, Marshall argued that Marbury was legally deserving of his appointment but the remedy was based on the Judiciary Act of 1789, which the Court had declared unconstitutional.

Technically Marbury won the case, but the Court had no constitutional power yet to enforce this decision by coercing Madison to comply. While the idea of judicial review would be used sparingly in the 19th century, it would become crucial to the legal battles of the 20th century.

Marshall found himself embroiled in politics once more in 1807 during Aaron Burr’s trial for treason. Marshall served as the judge for the trial, and, interpreting the Constitution’s definition of treason very narrowly, limited the trial in such a way that the jury found Burr innocent. The public was furious, but Marshall had once again shown the independence and potential power of the judiciary.

Other important issues decided during Marshall’s tenure included the sanctity of property rights, even if they conflicted with a state’s actions; that state governments could not attempt to control federal institutions through taxation; and the power of Congress to control interstate commerce and trade. Each case stressed the primacy of the national judiciary to decide federal issues. Marshall’s Court was also heavily involved in Indian removal

Marshall’s extended years of service on the Supreme Court played an important role in the success of the fledgling United States by providing it with a more powerful and adaptive national government than was possible under the Articles of Confederation

His close working relationship with the other justices inspired goodwill and respect, even among the justices who chose to dissent from his majority decisions. Even more important, his opinions became valuable tools for the later judicial activity of the Supreme Court. Marshall served on the Court until his death on July 6, 1835.