|

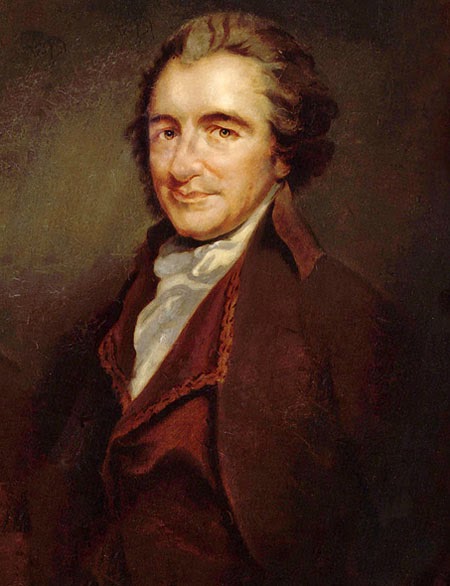

| Thomas Paine |

Thomas Paine, the English pamphleteer who helped spark the American Revolution and later played a central role in the French Revolution, remains a controversial figure, hailed by many as an “Apostle of Freedom” but disparaged by others as a drunken atheist and radical troublemaker.

Paine was born in Thetford, an English country town, where his Quaker father, Joseph Pain [sic] was a corset maker. Tom was well read, but his formal education ended at age 13, and his early efforts as teacher, tobacconist, tax collector, and even husband mostly ended in failure.

In 1772 Paine met Benjamin Franklin, then Pennsylvania’s colonial representative in London. Armed with letters of introduction, Paine set sail for Philadelphia in October 1774. Although a novice writer, Paine was hired by Pennsylvania Magazine, where his essays boosted the monthly’s circulation.

|

As tensions between Britain and rebellious colonials escalated, Paine began formulating his own long-held ideas of freedom and tyranny, inspired by such Enlightenment figures as John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Paine’s pamphlet Common Sense, published in January 1776, was a huge best seller.

Written in simple, forceful language and modestly priced, his passionate attack on hereditary monarchy and support of human freedom was read by perhaps a fifth of all Americans and inspired the Second Continental Congress’s Declaration of Independence that July.

As hostilities commenced, Paine wrote The American Crisis, a series of articles intended to bolster patriot resolve. George Washington used Paine’s opening salvo, “These are the times that try men’s souls,” to inspire his poorly equipped troops on the eve of a Christmas Day, 1776, victory.

By 1781 Paine was employing his pen to promote French-American alliance and secretly publicizing Washington and other leading Americans to earn desperately needed funds. In 1785 Congress granted Paine $3,000, and New York officials deeded him a New Rochelle farm.

Always restless, Paine traveled widely in the late 1780s, trying unsuccessfully to finance construction of his patented design for a new kind of iron bridge. He also found time to pick political fights with both sworn enemies and allies in the United States, Britain, and France.

In an outburst of political activism, beginning with his February 1791 publication of Rights of Man, a human rights manifesto, Paine became a principal defender of France’s ongoing revolution.

This would result in his 1792 election to the French National Convention, where he arrived in September, steps ahead of an arrest warrant issued by Parliament for “diverse wicked and seditious writings.” Found guilty in absentia, Paine would never again visit his native land.

Although he never spoke fluent French, Paine was acclaimed a national hero by adoring crowds and soon was helping devise a constitution for the new French republic. Meanwhile, as the Terror deepened and thousands fell victim to revenge killings, Paine audaciously opposed plans to execute King Louis XVI of France.

In December 1793 he was imprisoned in Luxembourg, a palace-turned-jail, where he would remain under constant threat of execution for 315 days. His health broken by incarceration, Paine nonetheless wrote The Age of Reason

Paine returned finally to his adopted homeland in 1802, after long-time admirer Thomas Jefferson became president. In his final years, Paine regularly attacked Federalists as opponents of liberty and endured accusations of atheism that alienated him from many old friends.

At his death in New York, he was almost as poor as he had been on arriving in America 35 years before. Even after death, this citizen of the world remained notorious. In 1819 an English admirer removed Paine’s bones from his New Rochelle grave. To this day, no one knows where Tom Paine rests.